The first rule of measuring your innovation performance is to recognize where you are. Innovation teams in immature organizations do not have a repeatable model for generating revenue and should work on other things first—and fast. You can’t manage a portfolio until you have one.

So, if your mandate is only to deliver “new ways of working” you will struggle to demonstrate value because the metrics are inevitably squishy. Move as quickly as possible to a model where you have an explicit commercialization mandate.

For more advanced organizations, the most important metric of an innovation portfolio is net new revenue. But capturing that revenue often depends on other parts of the company. Your team may have an explicit commercialization mandate and revenue target, but still lack a clear model for where new and proven ideas go, and when. Where: Do they go into the business, are they spun out, sold, or set up as new divisions or P&L lines? When: Does this change happen after MLP launches or after a certain financial benchmark has been reached?

Align with Internal Priority

To get to the right answers to these questions, you have to ask them early, and in a different form. Getting things to market takes conviction and ownership, which must be established earlier. If the best place for ideas to go is back to their owners, that ownership must start at the source, and the question is reframed as Where do these objectives and ideas come from?

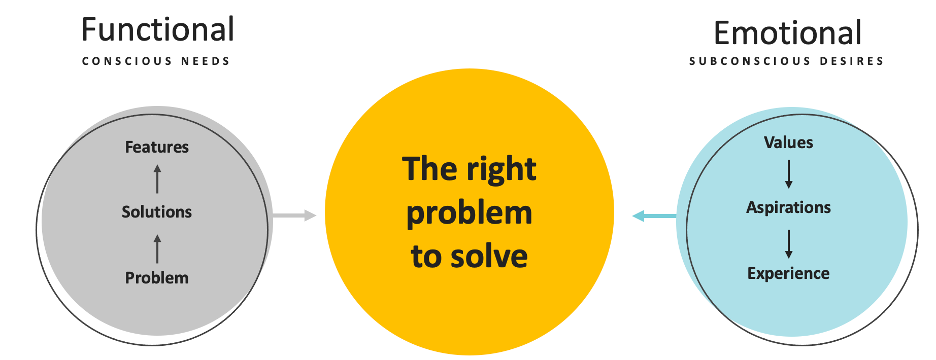

Engaging the business early ensures that priority is as important a consideration as the famed trio of feasibility, viability, and desirability. Think of priority as the internal version of desirability, requiring the same kinds of empathy and solving for emotional needs and complex real-life context. Our trusted research methods for looking outside-in and seeing the world through our customers’ eyes can also help us understand internal, organizational needs and acceptance criteria. Here are two:

Solve for Functional and Emotional Needs

People make decisions emotionally, then rationalize them with data. We assess radically new scenarios by leaning on a reference narrative. So do the groups of people who make decisions for organizations. All innovation work has jobs to be done, both for the good of the organization and the advancement of the individual people involved. Client empathy aims to understand those individual, emotional needs, and helps craft the compelling narrative that helps us resolve uncertainty.

Understand Problems at Multiple Scales

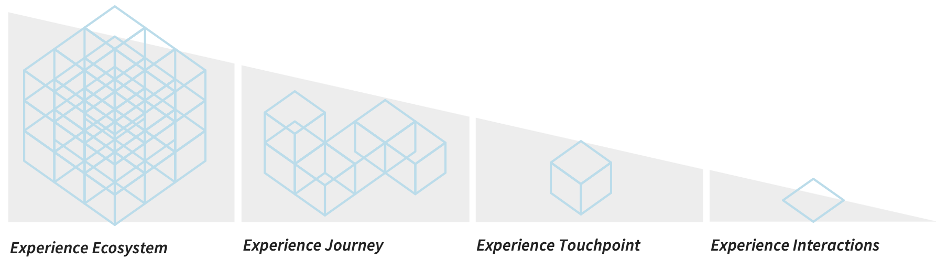

Solving for priority means you design to meet individual and organizational terms of acceptance: Where will this live and what business functions—current or new—will need to be deployed to effectively serve new customers. How big must the prize be? We have worked on projects where $50 million in new annual revenue was the goal; and others where 10 times that was not big enough. It is critical to know that target at the beginning. A design challenge sits within a business challenge, which sits inside a market challenge. This is analogous to how we design experiences:

• Solve the stated problem: Discover unmet needs and design something valuable to customers.

• Solve the larger business challenge: Design something that can be built and operated as a business to meet the technology team’s specifications.

• Solve the biggest, market challenge: Set the business up to win in a dynamic market. Even within the design challenge, anticipate the CFO’s scrutiny: Map out the business case, competitive position, and path to market. Be very clear on risks and known uncertainties.

In addition to these frameworks, borrowed from CX design to look internally, we have discovered some best practices in portfolio governance that help align priorities and keep innovation strategy and business strategy and operations close.

Tell a Coherent Story

Your portfolio should align with a vision or hypothesis about your organization’s future, and the cluster of initiatives should point in that direction. Partners in the business should recognize their needs and goals in the work you’re pursuing. Initiatives should sit relative to each other on some meaningful scales, not be individual and arbitrary search parties out hunting for revenue. Make sure people don’t get lost in the details.

Navigating uncertainty depends on a compelling narrative created out of uncertainty. Innovators find confidence in possible futures more like lawyers than like economists: They reason a way to the most likely story of “What’s going on here?” (For more on reference narratives, and decision-making in conditions of Radical Uncertainty, I recommend the book of the same title. For a more personal and poetic take on living in uncertainty, Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost.)

A strong strategic compass may not be the key instrument: In many companies there is a strong counter-argument that you should move fast, try everything, and let the market be your brain. Tolerate a high in-market failure rate. Your story should fit the world you operate in. My metaphor for this is reproductive strategy: Are you a tiger or a frog? Do you want to raise one or two cubs to adulthood, or spawn hundreds of eggs and let 99.9% of them die? I work best in the former strategy because it places value on strategy, and learning, and delivers durable rewards: Companies like Apple with the conviction to place fewer, better bets have stronger brands and can drive passionate loyalty.

Manage a Portfolio of Risk

Distribute initiatives across a horizons model so that you have some strong bets and some long bets. Consider time-to-value as an essential component of this. Most innovation organizations risk being shut down after two years if they have not met their targets, so some bets should deliver immediate value.

The key here is to be responsible in your approach. It takes a pragmatic confidence to know when to bet appropriately or fold when necessary. Mavericks know when to stick with a long-odds, high-reward, bet-your-job bet. They often earn that through being quite conservative about risk and having a track record of successes.

Measure Everything. Define Value Broadly.

You should measure as much as possible, so that your qualitative research has structure that the business understands. Count up the number of customers spoken with. Tally the hours of interviews, insights, opportunities, ideas, pilots.

Take credit for killing ideas that don’t work, especially when you’ve been enlisted to validate some expensive build that was already approved. If you kill something that saves the organization $5 million of development costs, claim credit for that $5 million.

Note: It’s crucial to be impartial about the data you are working with. “We tend to happily accept good results, which are confirming our biases,” HBS’ Stefan Thomke tells The Resonance Test. But when confronted by a “bad” result, he notes, “we challenge and thoroughly investigate it.”

Feed the Learning Organization

It’s essential to learn from failures, as tests of market potential and internal capability and fit, and apply those lessons to the next project. Get to a “saturation of insights” across multiple projects, so that over time the starting point for each project is more and more advanced, with clearer hypotheses. Build a complete and complementary customer model out of your qualitative research and your marketing team’s quantitative research.

Push Your Best People Forward

One model is to treat the innovation practice as an accelerator for high-potential people. Often a stint in strategy serves this purpose, so innovation might be smartly put in strategy. However, it doesn’t really matter where the practice sits. Design might be an option as well. EPAM has thought long and hard about how to nurture our best people, in a learning environment, as a means of pushing our business forward.

Take a More Disciplined Approach

With an uncertain economy closing in, we’re moving to a moment when discipline is going to be a major part of innovation. The balanced portfolio probably focuses on current business, and finding efficiencies and greater value at the core, and reflects a reduced appetite for transformation. The companies that will succeed will be those that measure and learn and use that data to chart the course.

Let’s Talk about Leaping the Highest Hurdle

All this rigor is essential because an even greater innovation challenge awaits those innovators at the largest companies who have been lucky enough to launch new $100 million businesses. At many Fortune 20 companies, the highest hurdle comes when successful new $100 million ventures are folded into the regular business and buckle under the weight of a large organization’s operating costs. This problem seems either obvious or intractable: “Stop doing that!” is not always workable, but otherwise the problem seems intractable, or not even an innovation governance challenge. I welcome your suggestions. Let’s talk!