It's 2021, and every organization is thinking about navigating change. The fact is, COVID turned many strategies and business models upside-down and made us realize that we’re neither as nimble nor as digital as we thought we were, or need to be. As Amy Wilkinson, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, recently told Forbes: “In today’s economy, the strongest companies are pivoting. But they are doing it at the speed of startups. Entrepreneurial thinking needs to be a part of every company’s 2021 plans.” The pandemic showed us that the need to do something dramatically different can come suddenly and without warning.

It’s a big difficult prospect, pivoting, one many people think and talk about but few manage to pull off successfully. How do businesses set a new target? And what does it take (really take) to hit it?

On the one hand, speed is essential to navigating change… but it's not enough when companies need to pivot.

Some say that all you need is speed. Yes, on the one hand, speed is essential to navigating change… but it's not enough when companies need to pivot. When companies choose to, or are forced to, change direction, setting a trajectory for the new target requires a couple of things in addition to speed: (1) strategic readiness; and (2) good aim. Without this trio of skills, you may end up with what a client of ours called a “perfect landing at the wrong airport.”

If you’d like to know more about the art of pivoting, read on. I’ll share three essential forms of pivoting and talk about how you and your organization can build your pivotal superpowers.

Three Pivots

Pivoting is not just an avoidance move. A successful pivot is a motion toward a new target. Moving forward requires three areas of clarity. To navigate well you must understand:

• your playing field

• your purpose, and

• your customers (current and/or future)

Of course, this knowledge must be deployed in the proper context. Done properly, these three elements will be embedded in the following three types of pivot.

Pivot One: Redirecting

Redirecting is the most common pivot. It’s often about responding to a threat or an opportunity by changing direction by redirecting or re-calculating, as our GPS systems tell us. This could mean going to a new target or going to the same target by a different route.

The superpower this requires is vision—the ability to see and evaluate your options. To have options in the first place, you have to be realistic about the real gaps you have to close and fully commit to closing those gaps. The question “Is it possible?” must always balance against the question “Is it necessary?”

The question “Is it possible?” must always balance against the question “Is it necessary?”

Companies that are retiring massive amounts of tech debt are also leaving behind terribly constrained ways of doing business. This opens up new possibilities you can capitalize on for customers. The good news: These efforts are backed by some superb modern operating models. Perhaps nobody was more ready for 2020 than the operationally excellent Walmart.

Walmart was not planning for a pandemic, but COVID accelerated trends that were in motion anyway, and it made some changes more permanent. The retailer has been working on pick-up for five years. They were ready for the demand that exploded this year. And the experience is so well executed that, even after the pandemic, for lots of customers it will stay the preferred option.

It can seem like Walmart got lucky. Or they were just in the right place at the right time. I don’t think that’s an accident. You can actually manufacture luck; it’s just where preparation meets opportunity. Preparation includes flexibility. It can also mean versatility of cross-trained people, or reconfigurable spaces, or responsive supply chains. Recognizing opportunity comes in seeing things others don’t, or finding the meaningful problems to solve for customers.

Pivot Two: Return to Purpose

Charting a trajectory into unfamiliar space is a battle against arbitrary judgments. We need to understand “Why this and not that?” One of the deans of business strategy, Michael Porter, says that the essence of strategy is choosing what not to do. He also says, “The company without a strategy is willing to try anything.” Porter means that as a problem, not a celebration of entrepreneurial energy.

“The company without a strategy is willing to try anything.”—Michael Porter

Consider a project we worked on with Fisher-Price a few years ago. Fisher-Price travels has an 85-year history of creating innovative children's products in line with children's development. But despite a strong legacy, Fisher-Price wanted to reinvent itself to connect with millennial parents, and to respond to our screened-in information age.

The challenge of our project was to help a legacy company understand how it needed to refocus the company and culture and find the new version of its true self. To accomplish this, we embarked on a project looking at business, technology, and cultural trends around parenting. We named this project “The Future of Parenting,” notably, not “The Future of Toys” or “The Digital Future.”

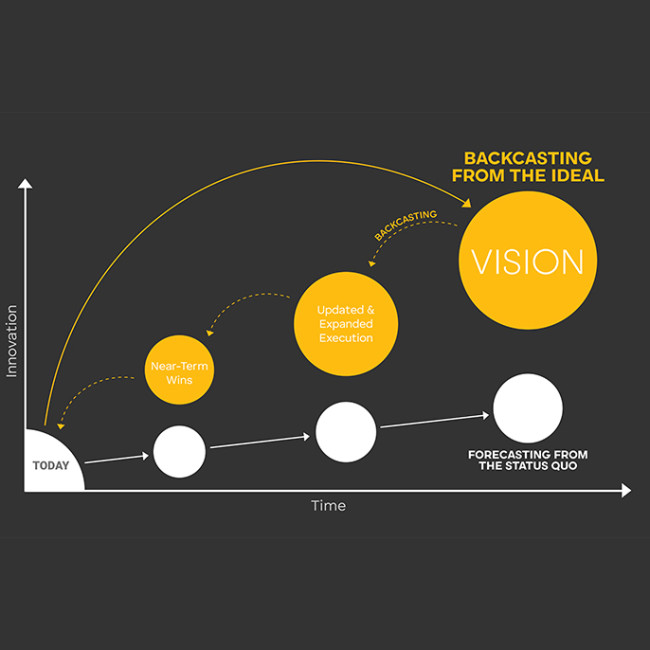

Our six big insights led us to a strategic vision for the role technology can play in the lives of parents and in the business for Fisher-Price. From this vision, the team backcasted a roadmap of product changes to set Fisher-Price on a new trajectory to reach its vision.

Embedded content: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BPidRZ_F5Y&feature=emb_titlePivot Three: Product to Service

How do companies make the pivot from a design language and operating model built around making and selling stuff to one that's based in services? In the delivery of services, which is essentially investing in relationships.

Working on Audi on demand, there were four important principles that drove it: (1) design for emotion; (2) design a system; (3) learn how to prototype the experience not the product; and (4) operationalize the ideal vision.

Audi is one of the great global brands. At the heart of the Audi brand is great design and engineering. The company came to us for help designing a premium mobility service because they realized that things are changing. They saw a distant but clear need to change based on a trend in consumer preference. People value experiences more and more and stuff less and less. Sometimes no matter how much you like something, the experience of ownership can be a hassle.

How do you prototype an experience? The short answer is you pretend.

To start, we needed to understand what the brand should stand for as an experience. At the beginning, this was a mystery. When moving from a product to service, you sometimes need to create new qualities of the brand. To get that right, you have to design for emotion. Getting to the right idea means coming to it from two directions: (1) the functional and pragmatic needs; and (2) emotional needs and values. Many companies, especially those with a strong engineering culture, do the first one really well. They understand people’s functional needs, and they debug and iterate a well-engineered solution. But people won't love a service unless we also design with alignment to their values and aspirations.

So we paid attention to the moments with a potentially huge impact, or a halo effect. The things that, if we got them right. could make the whole experience feel magical or, if we got them wrong, could make the whole thing feel like a failure. We assembled an ideal experience, and looked at failures and contingencies, in a co-design process with customers. We included lots of scenarios about bad things happening because service experiences are delivered through day-to-day operations and bad things can happen.

We thought through the overall experience, and paid great attention to every detail—but it wasn’t not enough to have each little detail be right; they also need to fit together, to demonstrate a singular service vision and make sense as one operating model. So we looked at it through the lens of systems thinking.

We carefully mapped out where those delight factors would show up in the experience and worked to eliminate the most consequential pain points. And at the end, we worked to operationalize this process, to make it repeatable and efficient. That is: We prototyped the experience, which is kind of an odd notion. How do you prototype an experience? The short answer is you pretend.

Prototyping is like putting on a loosely scripted play. The action that the customers see on stage has to be believable, polished and complete. The chaos that may be happening backstage doesn't matter. For this, you don’t need a lot. In our case, the entire IT back end was an Excel spreadsheet; the call center was a phone in my pocket; a little web app was installed on customers’ phones; there were two cars.

Speed in decision-making, in making the right decisions, is the best kind of speed.

Prototyping is also like designing a game: You have the game board and the pieces (cars, uniforms, the bare minimum software, rough scripts) and the rules—the contractual terms that you set up with customers vetted by the legal team, and a financially viable pricing model. Of course what matters in a good game is not the thing but the experience of playing. If the rules work and the people understand the rules and enjoy playing, it suggests we have a viable service experience.

I mentioned how services are more vulnerable to failures than products, which means designing for recovery: This is essential, and recovery is almost always in the hands of people. Much of the work we did to operationalize and scale involved managing the human variability, both from customers and employees. People are essential in a multi-touchpoint system, even a highly automated one. After the technology fails, it falls to people to recover. If someone contacts a call center, it’s probably after something else has gone wrong.

This service is live in close to 50 cities across the world. We designed it from the outside in, from the customer first. Because to navigate this kind of pivot, the superpower you need is customer intimacy.

Three Is the Magic Number

It takes all three of those superpowers to pivot properly. You need vision of your playing field, to understand what your options are. You need clarity about your purpose. Purpose helps you choose the right opportunities and decide what not to do. You need customer intimacy to build tight relationships and loyalty to meet your customers in their future. Together, these give you the smart adaptability that can become like muscle memory.

The goal is not to pivot once and reactively, but to do it opportunistically and repeatedly. Great companies are not just able to pivot but are constantly in search of the new opportunity, ready for the emerging threat, and of course, fast. Fast because they make the right decisions, and because they manufacture luck by being prepared and recognizing opportunities.

Speed in decision-making, in making the right decisions, is the best kind of speed.

Illustration by Natasha Polozenko