Many—too many—organizations have developed an emotional attachment to the idea of “failing fast”… without understanding that the mere accumulation of failures is not, in itself, an innovation strategy. Some fetishize failure because it sounds the way startups talk. The emotional appeal is also strong: So many people and organizations are petrified of failure that giving it a big bear hug feels like courage. But giving the impression of not being afraid is not the same thing as being smart.

The prevailing attitude toward failure revolves around generating numerous hypotheses, untethered to any rigorous form of testing. Planting a thousand seeds in the hope that one will grow is not a good use of resources.

You can do better. You can investigate fast, and get to early answers sooner. You can make failure tolerable by bounding it and designing experiments for learning first. Learning organizations tolerate failure because they fail instructively.

The Many Faces of Failure

There are many ways to fail. Each time we do it, it seems like a unique event. We think the scariest way is Hemingway’s description of a lost fortune—“Gradually, then suddenly”—because it tells of a fall that became unstoppable before it was detected.

We hear many clients express an earnest commitment to getting better at failing fast, to which we reply something along the lines of: “But not on purpose, right?” To be sure, there are many worse ways to fail: slowly, on an epic scale, inexorably, mysteriously. Perhaps even worse than outright failures are those deeply-invested projects that occupy an undead zone—not even clearly successes or failures, and never killed off or endorsed, because nobody knows what they’re supposed to achieve.

So sure, if you’re going to tolerate failure, it’s best to do it early, quickly, and clearly. And without doubt, organizations with no room for failure or exploration will struggle to establish a culture of innovation. Three things are needed to fail productively: (1) the ability to proceed with limited information, not hard proof, in advance; (2) adaptability to new learning; and (3) your approach should generate a surplus of opportunities and ideas.

Surplus

Let’s think about surplus. An abundance mindset—faith that latent and unmet needs are out there to be discovered and fulfilled—can help fuel growth. Confidence in our ability to come up with options and alternatives that we look at critically, to both sharpen our judgment and focus our plans, is the goal. Your approach can generate this surplus if it asks relatively open questions—the kind that can’t be answered “yes” or “no”—and if it draws insights from direct research with customers.

Surplus means that “failure” is much more often a pivot to a new space, not a complete dead end. Downselecting makes you smarter. Across a portfolio of innovation work, this surplus produces a flywheel effect of momentum and impact.

Three Things to Do

If you’re going to be more than a fast failure in the business world, we’d recommend that you engage in the following three activities:

Tolerate uncertainty. It’s important to be honest about what you don’t know, and to challenge what everyone knows but might not actually be the case. Uncertainty is the guest that never leaves. Better to get to know and deal productively with the lurker rather than simply pretend you’re all alone. Uncertainty is especially welcome at the start of a project, when it can inform a research agenda. Examining “what we know” and “how we know that” can sharpen conjecture into testable hypotheses, and lets you invest progressively to manage risk.

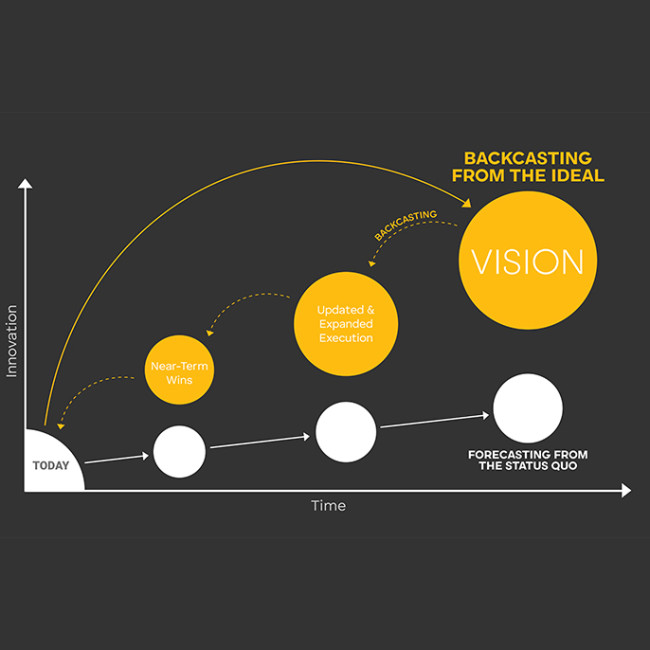

Cut your losses. Make better decisions, earlier. Progressive investment helps avoid two sunk-cost fallacies: financial and emotional. The second shows up as magical thinking—the belief in something because we want it to be true. A clear, stage-gated process maps key checkpoints that are timed to key insights, providing a roadmap and confidence that scales in line with, not ahead of, investment.

Celebrate learning. We would recommend celebrating learning (not celebrating failure). We would make sure that you’re not being too agile. Oddly, an agile approach that does not generate surplus will tend to become iterative trial and error (Bring me a rock. No, not that rock. Bring us a rock.). In that context, work is guesswork, failure is probable, and should not be celebrated. As Jeanne Ross and Nils Fonstad, two researchers at MIT’s Center for Systems Research, suggest: “Instead of failing fast, companies should ‘learn fast’ by designing initiatives to ensure learning, instead of hoping that failure leads to insight.”

Healthy Innovation Focuses on Learning

You are certain to fail, probably many times. The hit-rate on innovation is far from 100%.

Some organizations are so intolerant of failure that talking about it at all in positive ways is necessary to change the culture. In this context, getting good at killing ideas faster, before they’ve burned a lot of investment, is probably the best first step.

The most constructive ways to do this also minimize the harms—sunk time and investment—and reap the learning benefits of failure. These are the best ways to make failure acceptable to leaders. When you have a healthy culture of innovation, failure looks very different:

• Fewer initiatives fail completely by running into blind alleys. Ideation grounded in customer insight always offers context, alternatives, and a chance to pivot away from your original hypothesis to the right answer.

• Uncertainty and risk are measured, and de-risking is a key element of validation. A gated process sequences investment prudently, and clear and consistent go/no-go metrics help everyone understand why something is failing. This transparent process also makes it more acceptable to learn as you go and acknowledge uncertainty.

• Learning is cumulative. Across a portfolio of innovation, individual insights about customers and market potential build up a common ground of understanding. Newer projects start from a better-informed place and move faster. A surplus of insights forces you to prioritize, and to understand why, strengthening your judgment in early decisions.

If you aim to succeed, the thing you should be doing fast is not failing, but learning.