Localization

This year’s economic disruptions–reorganizations of trade and supply chains and localization of purchasing and travel–are part of a greater shift away from free market thinking and towards a new understanding of how our economic system works, with deep implications for what it means to be competitive in the global market.

We’re in the middle of a paradigm shift in the global economy, one that began years before COVID-19 massively disrupted supply chains and consumer demand. A better way to understand this moment and what it means for business is as the waning of an ideal that has shaped how we do business for decades: It’s the end of the global free market as we know it.

We’re in the middle of a paradigm shift in the global economy, one that began years before COVID-19 massively disrupted supply chains and consumer demand. International trade, travel, and trust are contracting, and the pandemic seems like a logical catalyst; our lizard brains reacting to foreign threat. But really big shifts–we call them tides–never come from just one direction and take many years to build momentum. A better way to understand this moment and what it means for business is as the waning of an ideal that has shaped how we do business for decades: It’s the end of the global free market as we know it.⁷²

The idea of the free market came into vogue in the mid-20th century, and when the US emerged from the Cold War as the dominant force in the global economy, it was the macroeconomic doctrine that set the terms for the period of rapid globalization that followed. But the orthodoxy was shaken by the 2008 financial crisis and has suffered deeper blows in the last few years; internally undermined by shifts in prevailing economic thought and externally challenged by a global wave of populist, protectionist politics. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is gaining traction in Europe ⁷³, China’s neomercantilist strategy has delivered unquestionable economic success, and the US–itself dabbling in populist protectionism–no longer unilaterally sets the global economic agenda. Analysts and historians have likened the present shift to what happened after World War I, when the world turned away from Victorian-era globalization towards a decades-long period of market retreat.⁷⁴ʼ⁷⁵

The existential angst of this transition is compounded by the pandemic’s economic shockwaves, Brexit, and the sharpening trade war between the US and China. These present uncertainties have hastened trends already put into cautious motion by the paradigm shift—contracting supply chains, tightening digital and physical borders, regionalizing markets.⁷⁶ It would be an exaggeration to call this the death of globalization. Rather, it’s a moment of realignment and disruption as we enter a new phase, one no longer completely characterized by free market economics.

What this means for businesses is that the rules are changing. Over the last 30 years the international economy oriented itself around the free and swift movement of people, goods, and data across borders and around the world. Strategic principles like efficiency came to define what it meant to be competitive. Now we’re on the cusp of a new regulatory environment, and the dynamics are changing. Strategic principles like adaptability and resilience ⁷⁷ could be what defines competition in a more closed and protective international market.

The goal of the free market approach has been to decrease friction in the market to promote competition. Spindly supply chains were a secondary effect shaped by the competitive efficiencies of manufacturing consolidation and/or single-sourcing, specialization, lean operations, and just-in-time delivery. Passing a stress test like the pandemic wasn’t in the design brief, but the system-level failure felt by both consumers and countries this year is driving the argument that it should be. Companies are concerned about reducing dependency on China, and governments have focused on supply chains as an issue of health sovereignty and national security.⁷⁸

Supply chain issues, in combination with economic shutdowns that took an extra toll on small businesses, have drawn consumer attention to local goods, especially in essential verticals such as groceries,⁷⁹ and economies.⁸⁰ Local tourism also saw an uptick this year as international travel plummeted.⁸¹ During COVID-19, international borders have closed to a degree that’s completely unprecedented in the modern era. US passports have always been something of an all-access pass to the world, an immense privilege Americans have shared with residents of just a few other countries and regions like the EU. But in July, an article on Medium⁸² went viral for calling US passports worthless, as almost the whole world shut their borders to US travelers.

Of course, the extreme restrictions of this moment will pass, but they are in line with an overarching trend of anxiety and conflict over immigration and border control that has been shaping international politics in recent years. A decrease in open borders is a major disruption to industries that have come to rely on international workers, from agriculture and construction to healthcare⁸³ and tech.⁸⁴

2020 delivered many different kinds of shocks to the cohesion of the global economy, and 2021 will be characterized by the reverberations. Businesses that manage to ride it out should be prepared to adjust their business strategy for a new, more guarded market environment. Eventually the world will find a new equilibrium, but it won’t look quite like the old.

2020 delivered many different kinds of shocks to the cohesion of the global economy, and 2021 will be characterized by the reverberations.

The Splitting Software World

Sam Rehman

SVP, Chief Information Security Officer

San Francisco, CA, USA

After gifting us more than 20 years of unprecedented connectivity, the internet has reached an inflection point. Mimicking our ever-increasing polarization—both national and international—this shift has been called a cold war of technology, though it goes beyond political factors. We’re seeing more nations move towards internet isolation—a segregated model of the web. There’s China’s Great Firewall, part of the greater Golden Shield Project, and Russia’s “sovereign internet.” Alongside the splinternet effect are the increasing pressures from industry and regulatory standards. The telecom industry has its own consumer protection restrictions, for instance, and China has passed laws around crypto standards and cryptocurrency that are targeted towards creating a segregated ecosystem.

The upshot for enterprises and consumers is a lot of complication. Better privacy and data-protection laws are good for users, but don’t help us track who has our data or what services comply to which standards across the internet. And conflicting regional requirements for how data is stored and accessed can also unintentionally undermine security. Software environments are complex networks of data, applications, and processes: If data needs to be stored locally (for example, in the EU or UAE) or applications must be run within a particular country (the case in China), those components end up duplicated or custom-built versions are run in different places. Companies are forced to rethink their cloud and data strategy for a sort of split-brain approach to IT–running multiple operations for multiple environments–that is hard to manage, and even harder to secure.

Standards may be muddy right now but your approach to resolving them needn’t be. First, recognize that these standards and regulatory measures represent significant, long-term investments on behalf of governments and regulatory bodies–they’re likely to stay and you should take them seriously. Build an IT and multi-cloud strategy that accounts for standards and regulations from the start–don’t try to make compliance a last step. Build a plan for data and security as soon as possible: Identify core assets and map your entire dataset to standards requirements so you know where and how to invest in the critical security controls and processes. Last, communication really is key. Bring your employees and clients on board and take this journey together–technical problems are only really a problem when they’re a surprise to anyone.

The New Frontier of Resilient Supply Networks

Vikrant Kamble

Senior Manager, Business Consulting

Philadelphia, PA, USA

Denis Grishin

Managing Principal, Business Consulting, Supply Chain Practice Lead

Philadelphia, PA, USA

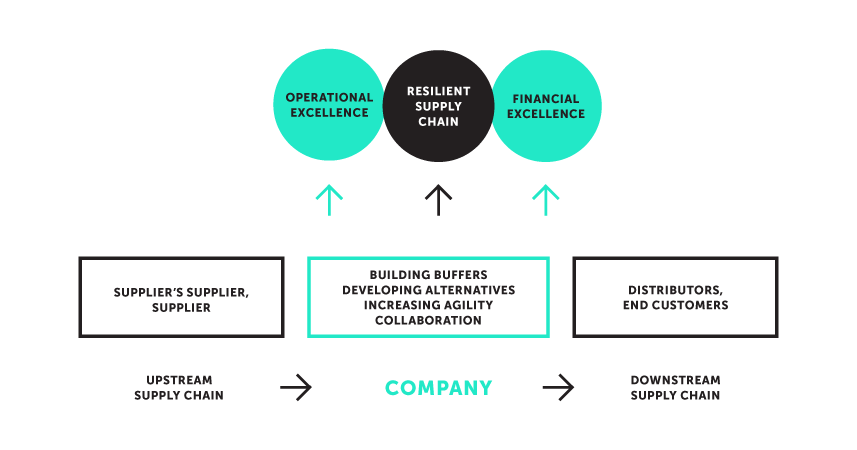

Supply chains are much more fragile than we realize. Disruptions can occur at many points along end-to-end supply chains, including within supplier networks, manufacturing, distribution networks, or markets. While companies have many levers at their disposal to future-proof their supply chains, in this brief piece we’ll focus on how to approach building resiliency into your upstream supply network.

Resiliency is the ability to recover quickly from adverse conditions. To build resiliency into your supply chain, look at these key characteristics when evaluating existing or selecting new suppliers:

Risk profile–the probability of shutdowns or disruption

Geographic reach and proximity to you and your end customers (Do they have alternative routes, or the ability to direct factory shipping?)

Excess capacity–the ability to absorb demand shocks

Capability to innovate with you (Can they develop ready-to-go packaging?)

Agility–the ability to reorient manufacturing capacity to current market need including substitute products (Are they nimble in adopting new designs and processes?)

Mature collaboration capabilities and communication protocols (such as safety standards, social distancing at work, or digital maturity)

To avoid further acute shocks, companies must transform their own supply chains and bring resilience as one of the key traits. Network mapping ⁸⁵ is a strategic step towards such a transformation, helping you gain full visibility of existing suppliers and their risk-mitigation strategies. Primary and alternative sites, routes, and activities, at least for tier 1 and tier 2 suppliers, must be documented. Here are key network-mapping activities:

• Conduct research by considering end-to-end value streams and physical flows⁸⁶

• Collect additional data (along with traditional KPIs–cost, lead time, and capacity–consider gathering risk profiles, probability of closing down, disruptions etc.)

• Go beyond your existing network (find alternatives and work with new suppliers)

• Rearrange your supply network with resiliency in mind

Tools like Elementum, Llamasoft, and Resilinc provide excellent visual representation of the existing and future resilient network. Companies must reevaluate their supply chains and partners on an ongoing basis. In the past, network optimization analysis have been done once in one, two, or three years. In the current reality we should be moving to a more frequent, and more granular, analysis. Identifying risks–shortages, failures, and delays–early enough will enable you to plan a swift response.

To sustain and grow, companies will be using this pandemic as a catalyst to develop a resilient supply network along with a new go-to-market plan.

64%

64% of companies in manufacturing and industrial sectors said they’re likely to reshore production and sourcing post-Covid.