There are fields in which, as my colleague Augusta Meill points out, expertise and judgement matter. These are the areas of life where we might need to be protected from ourselves, where we cannot trust our impulses or our own expertise. Areas such as taking care of our health or our long-term finances. Or, it is starting to seem, making choices about our college education.

In all these domains—healthcare, financial services, and higher education— there are technological forces at work disrupting the established structures of control. All three are areas where customers, if we should call them that, have more information and more control than ever before. The same technological trends are lowering the barriers to entry for new competitors and new offerings. Established companies are figuring out how to respond.

Healthcare companies are recalibrating to a more patient-centered approach, trying to treat patients in a more humane, holistic and empowered way. They are learning how to share control over the experience. But, as recent shifts in higher education have revealed, there is a distinction between control and empowerment. Healthcare would do well to look at where consumerization has gone awry in higher ed.

Control vs. Empowerment

It can be hard to share control without losing control. Universities seem to have gone too far, giving in to students not only on the definition of what is in their best interests, but on the ownership of the recalibration process itself. Students appear to be driving, and the results are unnerving.

If a university treats students as customers with all the prerogatives that come with that designation, they can lose control of the canon. The Atlantic’s “Coddling of the American Mind” cover story argues that students are leading a movement to control what ideas they are exposed to, and how those ideas are presented. This impulse to make education safe and unthreatening starts with protecting students from patently offensive ideas, but once it’s mobilized, The Great Gatsby and Ovid’s Metamorphoses can fall in for the protective packaging of “trigger warnings.”

Universities cannot be required to protect students from any potentially traumatizing idea. That is bad pedagogy, and as The Atlantic points out, bad for psychological health. School is supposed to be challenging, emotionally as well as intellectually. But comfort sells, and the market is competitive. Institutions of higher learning have always competed for students and tuition. The quality-of-life arms race is accelerating, with implications beyond the curriculum.

School is supposed to be challenging, emotionally as well as intellectually. But comfort sells, and the market is competitive.

Forbes legitimizes the expense of building rock walls and water parks as smart business for less selective schools. These attractive amenities may be driving enrollment among “lower ability students and higher income students” but something has to give. The economics suggest price sensitivity is increasing. Costs cannot keep rising as they have. An interesting contrast is how innovative hospital design has, as my colleague Yuhgo Yamaguchi writes in Harvard Business Review, reduced costs, increased patient satisfaction, and improved outcomes.

It is misguided to give students expensive toys; this may ultimately bankrupt the less selective institutions with unsustainable cost trends. It is equally treacherous to let students control the curriculum. As The Atlantic article reports, professors feel a “chilling effect on [their] teaching and pedagogy.” Will the best professors be driven out of the field by this culture? Are we running out of common ground between more demanding students and the teachers and administrators who are charged with their education and care? There is a distinction between empowering students and putting them in control of the experience. The same can be said of patients.

Are we running out of common ground between more demanding students and the teachers and administrators who are charged with their education and care?

The Ratings Game

While the argument for a patient-centered model for care is valid, the metrics by which we measure patient satisfaction may not be. There is power, akin to what is seen in academia, in the ratings systems that are proliferating in clinical care. This was another topic critiqued by The Atlantic last spring. You can rate your doctor or professor on irrelevant criteria (even hotness!) but even a general “patient satisfaction” score rankles doctors. As one doctor said to me about this trend, “I am here to save their ass, not kiss it.”

This September, President Obama leveraged metrics in a different way when he unveiled the government’s College Scorecard, a website that focuses on a more straightforward cost/benefit analysis. Good data on cost, debt, student outcomes, and graduate-earning power can help students and their families make better choices. A tool like this is is increasingly valuable as the cost of all options has risen dramatically while the ability to compare has remained opaque.

Healthcare in the ACA Era needs these kinds of pragmatic and transparent tools. They help empower patients and align them with their providers around a common goal: finding the best medical outcome at the most affordable price. Yet data alone does not serve to reform a complex system.

Common Ground, not Common Core

In a recent project, Continuum found that the values and processes of a design thinking approach can help create the kind of collaborative space essential to success. We put this approach to work with Boston College to renew their core curriculum with interdisciplinary courses that teach Complex Problems or Enduring Questions from multiple disciplinary perspectives (see this Chronicle of Higher Education article). This kind of change is as much about the journey as the destination. Educators, administrators, and students don’t necessarily want the same things, at least in the short term, but the methods of a design thinking approach helped create common ground.

As with students, so with patients: the right way to factor in their needs is by being inclusive and transparent, and by focusing on the common goals. Prioritize the improvements to their quality of life that also lead to better educational, or clinical, outcomes.

Design thinking methods help get the process right, because in healthcare, like in higher education, a decision can be seen as invalid if the process of getting there is considered illegitimate. The context calls for inclusive, consensual decision-making, which is a good fit for design. We work toward clearly articulated goals, we share and assess work in progress, we think out loud and iterate.

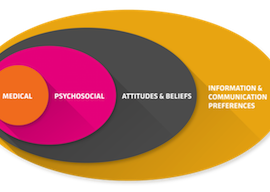

The lesson here is that we should not only work toward inclusive outcomes, but also exemplify that value in how we work. Service design is also a field in which expertise and judgment matter, so to solve for multiple stakeholders’ needs, we must make higher-order decisions based on evidence and targeted toward clinical (or educational) outcomes as well as the metrics of service experience or satisfaction. An empowered patient is our goal; that is not the same thing as a demanding consumer.