1.

It’s not impossible that in the past year you read, heard, and/or spoke about plant-based meat. Indeed, you may well have dug your hungry teeth into a plant-based burger, meatball sub, or breakfast sausage at one of our fine fast-food establishments in 2019. Big Meat is staking a claim in the plant-based game, and Beyond Meat had quite the IPO!

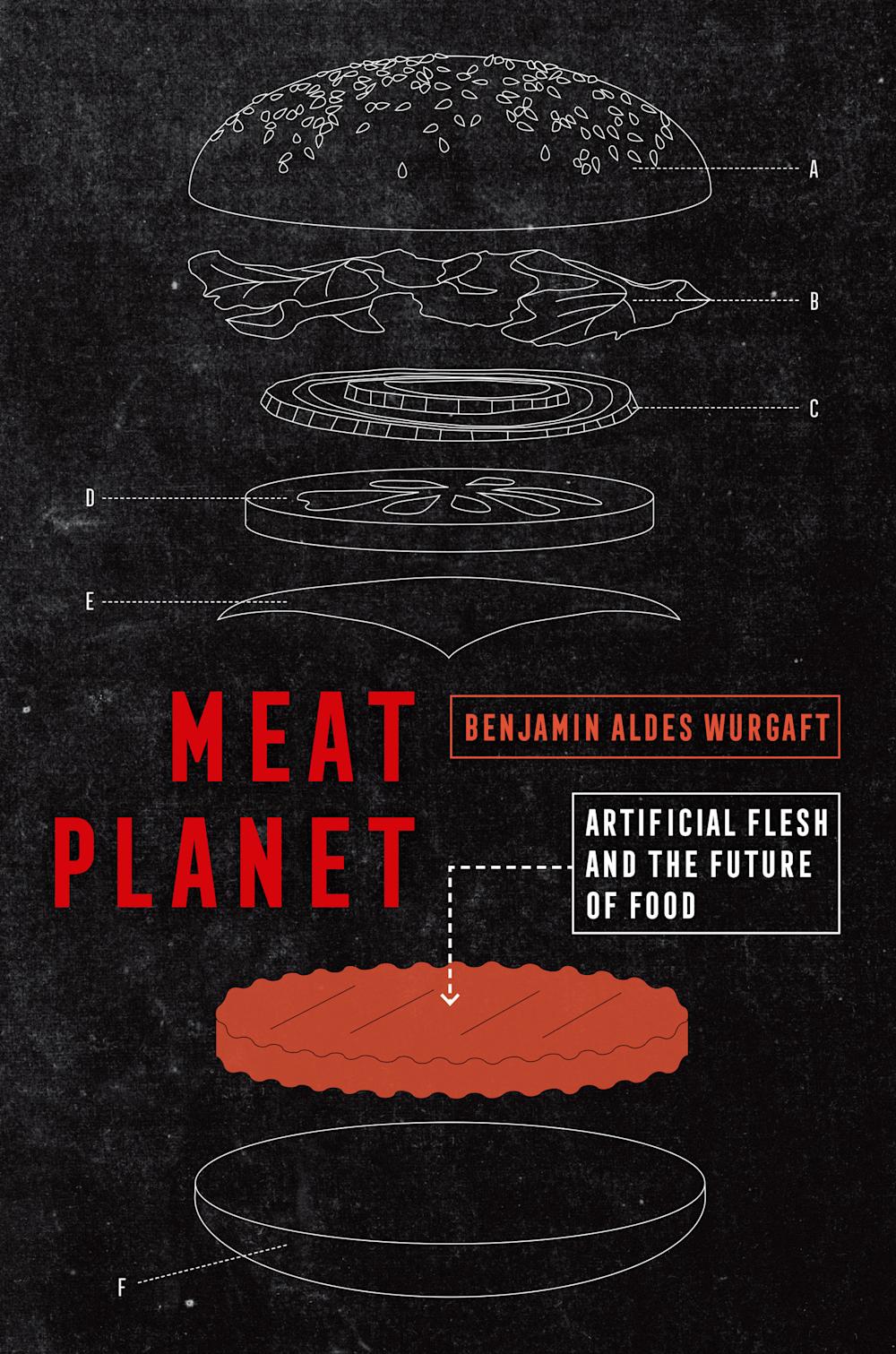

But there’s a genre of next-gen beef that you may not have pondered, and certainly haven’t tasted, that’s worth your consideration: Cultured meat. It’s a weird sort of protein, as Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft describes it in his book Meat Planet: “Laboratory-grown meat made of bovine muscle cells that proliferated in a bioreactor.” Ew, right? Right. There’s no denying the oddity of lab-raised meat, and yet it’s not just weird. The idealists say cultured meat could make humans healthier, cut down on carbon emissions, and decrease the amount of animal suffering in the world. The skeptics, like our neighbor Christina Agapakis of Gingko Bioworks, author of “Steak of the Art: The Fatal Flaws of In Vitro Meat,” doubt the viability of the project. They say that scaling cultured meat production is extremely problematic—"Cell culture is hideously expensive, not to mention technically difficult,” writes Agapakis—and that, if it can somehow be scaled, there might well be some bad environmental consequences (“techniques for making things cheap by making them scale have tended to shift costs to the natural world,” writes Wurgaft). Finally, there are entrepreneurs, innovators, and investors, for whom cultured meat promises to create lucrative business opportunities.

This is the world of Meat Planet: “Call this book a biotechnological nature walk, an assemblage of detours through the history of the future of food, a collection of mediations on meat, attentive not only to the ideas of scientists and engineers but also to the way they serve as catalysts for philosophical, anthropological, and historical inquiry.” In a loose bundle of essays, Wurgaft attends some conferences, visits a lab, and indulges in occasional bits of philology (“Protein is protean. The word ‘protein’ derives from ‘the first’ in Greek (protos), and it is as changeable as Proteous, the sea-god Poseidon’s eldest son. This is perhaps the most important thing to know as we turn to the question of meat’s definition and to meat’s shifting role in the human diet.”). It’s hard to say exactly where to stick Meat Planet on the shelf.

2.

The fact that Wurgaft throws both philosophy (Nietzsche, Peter Singer) and poetry (August Kleinzahler, Paul Muldoon) into his literary meat grinder impressed me, but I know this mix isn’t for everyone. It’s necessary to prepare these people for what awaits them and argue for its value because Wurgaft—with his learning and digressive prose—will be too much for many.

While Wurgaft is indubitably professorial, Meat Planet does not serve up professorial assurance. We instead get an informed outsider’s notes on an attempt to create something extraordinary. “Cultured meat is still emerging as I finish this book,” he writes, adding: “Promises are made on behalf of cultured meat, and chroniclers like myself measure out doubt and hope.”

There isn’t much of a plot here. Meat Planet is, in fact, a kind of narrative meatloaf, a collection of essays that are sometimes academic, sometimes journalistic, sometimes personal. They bounce between the central themes of doubt and hope. “Over five years I gathered a lot of doubts. They ran from heavy criticisms of the feasibility of cultured meat, made by scientists, all the way to laypeople’s gripes left in the comments sections of online news articles about cultured meat,” Wurgaft writes in a chapter called “Doubt,” and then, a few pages later in one dubbed “Hope”: “I followed the story of cultured meat because it spoke to a complicated corner of my soul. I had long been troubled over carnivory. It is ethical to eat animals? If eating animals is unethical, but I continue to eat them (reader, I eat them) what does it mean to live with that hypocrisy?” The effect of balancing hope against doubt creates a kind of readerly detachment. The extremes sort of cancel each other out. Wurgaft works hard to ensure that readers don’t ultimately pick one extreme, but understand both.

As an observer with no personal agenda—other than gathering a meaningful story—Wurgaft continually reminds us what’s at stake, who the players are, and what they stand to win and lose here. It’s pretty rare to have an unbiased chronicler keeping score in an innovation story. Often, the innovation narrative is about creating some kind of heroic tale for the purposes of selling something to someone. Wurgaft has taken a kind of oath to report what he sees as the truth.

3.

That oath is on full display, for instance, in the opening chapter. Wurgaft wakes up early in the morning on August 2013—4:30 a.m., Los Angeles time—to watch online the unveiling of the world’s first lab-grown hamburger (at a brow-raising price tag of $300,000) in London. He provides the play-by-play of the feed, introducing us to the main characters, particularly Dr. Mark Post, the Dutch doctor and physiology professor whose cultural experiments are backed by Sergey Brin of Google/Alphabet.

Wurgaft sees a promotional video featuring “senior biological anthropologist Richard Wrangham, who sits in his Harvard office. Book spines visible on shelves behind him” and he says: “The story of human evolution… is intimately tied to meat.” He talks about Wrangham’s Catching Fire, before informing us: “His book has been subject to discussion and debate among biologists and anthropologists in a way that the film I’m watching can’t possibly track. The tactical reasons for bringing Wrangham into the picture are clear. If Brin speaks for the promise of the new technology, Wrangham speaks for evolutional antiquity and the authority of science.” (Watch Post and Wrangham taking in the expertly shot video, above the atmospheric music and adjacent to some misty seascape scenes and see if you don’t uncritically buy every last syllable!) I particularly like how Wurgaft hits pause and talks about how there’s much debate about Catching Fire and then sends us off to a footnote—there are many footnotes in this book—for more reading!

The method of Meat Planet is to help us read the developments in the cultured meat better, slower, deeper than we would on our own. The notion of halting the innovation story to really think about what’s going on is, in fact, welcome. Human-centered design urges us to stop, step back, and take a more thoughtful look at what’s happening right front of us. Reading Meat Planet does something similar for the cultured beef world. Wurgaft argues that for cultured meat to work, things need to take a different tempo: “cultured meat needs a more patient form of capital” and “research should take place at the potentially slower pace of academic labs drawing on (one hopes) government funding.”

Most people in the innovation space aren’t looking to meditate on anything. Just the opposite. They’re looking to build. To test. To refine. To profit. To influence. The relentless pragmatism of innovation doesn’t look inward but forward. And it does it fast. Meat Planet, however, must be consumed slowly (there are so many ideas and references, so much scientific and philosophical detail, on these pages) and for the reader afraid of slow thinking, no matter what her professional affiliation, this is might prove a problem.

I think this is Meat Planet’s real value. By forcing us to stop and ask serious questions, it creates a pattern of ethical reflection—one that could extend off the page and into life.

4.

Wurgaft concludes his ruminations with a scenario in which he seems to find the most hope, and the least doubt: “pig in the backyard,” in which “urban neighborhoods communally raise a pig and eat the meat made from biopsies of its muscle cells, implies that we might come to regard a porcine individual—whose relatives we previously killed and ate—as living without our circle of moral concern.” He says this notion “speaks directly to my own imagination.” Easy to understand the appeal but difficult to know how to put a pig in every urban backyard. (There are an enormous number of pigs, cows, sheep, and other animals in the world; what about them?) He’s identified an ideal future state, but the real work, the most difficult work, would be to backcast it into reality.

I can imagine that this book would do as much good for an open-minded VC as it would for an open-minded biologist, entrepreneur, or PETA activist. The trick is, I suppose, finding such people who are curious and patient enough to give it a shot to endure the challenges of Wurgaft’s attention-demanding pages.

This is not a simple narrative that builds to some explosive denouement. The numerous digressions require much literary tolerance. Wurgaft is, to his credit, unwilling to be reductive in his thinking… which means, for instance, you might have to spend more time than you wish watching him work through a passage about promising, in Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, and the responses of several later-day thinkers to it. I actually dug that section but I suspect that others might feel another way about it, and many other such Meat Planet moments. What about you? After all you’ve heard about Meat Planet, would you want to pay a visit?