We just received some really good news on the coronavirus vaccine front. Pfizer posted early data that shows 95% efficacy and Moderna reported that their version of the vaccine was 94.5% effective. These results are a triumph of America’s culture of innovation and represent the fastest development of a vaccine in all of human history. These are significant data points… but before we toss our masks and roll up our sleeves, we must consider some of the challenges with the vaccine. I want to share some of these challenges, and plant a few seeds for near-term and longer-term solutions.

A Challenging Journey for Our Vaccines

For starters, the logistics for both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are daunting. Both vaccines require two doses delivered 28 days apart. Even after the vaccines are approved, it will be necessary to produce double the volume and to track who received which vaccine and when. This will have important implications for allocating scarce resources, and it will affect the timing required to reach a critical mass of vaccinated people. Never mind the psychological barriers to getting people to make time for a second shot, when they’re likely to feel or believe they are immune after the first.

In the US, we have some of the necessary infrastructure required for this kind of work, but nowhere near the capacity needed for a vaccine that acts like a large molecule-infused drug, in terms of its storage and handling requirements. The demand will absolutely dwarf that of even the most widely used oral-prescription drugs.

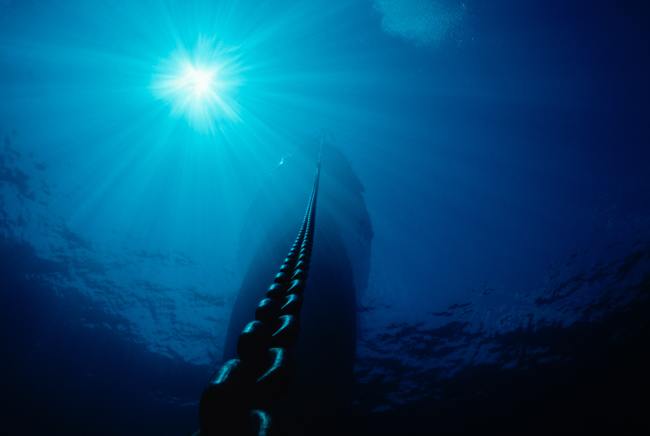

Another challenge with the Pfizer and Moderna approaches is that their vaccines have some pretty heavy storage and transportation requirements. The vials must be kept at -94 degrees Fahrenheit (for Pfizer) or -4 degrees Fahrenheit (for Moderna), a requirement that can be met either by specialized equipment and/or dependable and rapid access to dry ice. To put that in perspective: The dewars used to ship vaccines can be filled with dry ice (-109 F) but, at least for Pfizer, can only be replenished a maximum of three times. And if part of the shipping is done via airplane, the FAA limits the amount of dry ice that can be on board. Additionally, there just are not enough of these specialized shipping containers available at present time. Ultimately, these multiple needs mean that there are large swaths of the country that will be unable to handle the vaccine, and on a global level, there will be entire countries where it may be impossible to reach the people who are most in need.

Even at hospitals, there will be special handling requirements. The packages the vaccine will be shipped in can be opened twice a day (Pfizer), at the most. When moved to refrigerators, the vials can be stored for at most five days (Pfizer) or 12 days (Moderna) and cannot be refrozen. All of this will require specialized staff with the training and perhaps licensure to handle the vaccine—and those needs may vary at the state level because pharmacies are regulated by states. Hospitals won’t be able to hold a clinic and pack people in quickly and efficiently—social-distancing protocols must be in place—and I’d expect the process to be, on a per-patient basis, closer to getting a COVID test than a flu shot.

It will also be necessary to track the vaccines on their journey from manufacturer and out into the world. A detailed record must be kept of the storage and handling requirements were maintained all the way until the vaccine makes its way into human arms. These kinds of chain of custody and identity can be met by a select group of couriers—such as AmerisourceBergen’s World Courier business unit—but non-specialized delivery organizations such as FedEx and UPS won’t be able to manage it.

No matter who oversees the delivery process, there will be human challenges with these vaccines. The first is our fraught cultural moment. Our nation is now more divided in more fundamental ways than at any point in our history. A significant portion of our population sees masks as an afront to their freedom, despite overwhelming and authoritative support that masks do in fact limit the spread of COVID. Additionally, there is a decent chunk of Americans who mistrust vaccines. Persuading enough people to accept the vaccine to achieve population level control of COVID-19 will take some real thought and effort.

One last challenge emerges when we consider the overall journey of the vaccine itself, how it gets from factory to arm. That last step involves our frontline health care workers. They have been fighting the virus since early spring, and they are tired. A nurse friend of mine contracted COVID from a patient and asked her boss to transfer off of the COVID unit—knowing it may cost her job… an outcome she hopes will be realized. And she’s not the only health care provider thinking of leaving, or actually doing so. The sacrifices our health care workers are making are valiant but unsustainable. Our health care workers need this vaccine to be here faster than it is likely to arrive.

Solutions for Today—and Tomorrow

What’s needed to vanquish many of these challenges are partners with a broad and deep set of technical and human expertise who can make great use of the limited resources available.

There are a few solutions we could implement “today.” Let’s imagine that both Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines are approved. Perhaps rather than making their products individually available, could these two companies cooperate to reach the maximum number of people most quickly? For instance, Pfizer could focus on academic medical centers and urban areas likely to have the requisite infrastructure, while Moderna pursues suburban and rural areas (I’d be willing to bet they’d receive an anti-trust exemption for doing so). Moderna could do one better and create a mobile vaccination offering—despite the complexities of the therapy, we already have some mobile medical infrastructure that could be deployed.

On the behavioral front, I draw some inspiration from none other than the king of rock, Elvis Pressley, who in 1956 received Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine on the Ed Sullivan Show. Who is Elvis in today’s world? Is it Beyonce? Taylor Swift? Having a worldwide celebrity, or even several of them, roll up a sleeve might help persuade Americans to get the vaccine.

The solution must also be GENTL. (At the start of this pandemic, my multi-disciplinary and brilliant colleagues joined #TogetherAsOne in an effort that yielded, among other things, the Good Enough Not Too Late or GENTL Mask.) Could we create a GENTL Dewar—something that provides enough of a thermal benefit to allow these vaccines to be deployed to otherwise inaccessible parts of the world? In India, where 80% of the population lacked access to a refrigerator or reliable electricity, food spoilage was a constant problem. What people needed wasn’t a fancy stainless steel French door refrigerator freezer. They needed something simpler; after all, cooling some food, if only for a day or two, was far better than letting their food soil. The solution was the Chotukool, a 45-liter thermoelectric cooler that was portable and ran off a battery. I’d bet we can modify some igloo coolers as a low-cost rapid way to deploy vaccine transport dewars.

When we look to solutions “tomorrow,” many more things become possible, given some time to bring new technologies and insights to bear. Blockchain and sensor technologies could enable the kind of tracking and tracing that invariably will be required. A deep understanding of distribution networks and how to optimize them can help efficiently and predictably move these precious packages along their journeys. Expertise in people—not just in patients or physicians, but in nurses and pharmacists and caregivers; all of the people touched by this vaccine—can help design the kind of experience that keeps everyone engaged and increase the likelihood that patients will follow up with second doses. This will support the longer-term tracking that will be essential to defeating the virus and weaving the data fabric that will enable the necessary sort of follow-up analysis.

Combining all of these capabilities may even help identify new manufacturing methods that enable us to bridge the gap between demand and vaccine supply or help build new kinds of transportation containers that cost-effectively extend cold chains into rural communities and developing countries. When you bring such a broad range of talent together, great things are possible. We are on the cusp of a vaccine; let’s get it out into the world into as many arms as possible as quickly and as we safely can.

Teaming Up to Deliver

So, with all that said, the Pfizer and Moderna news is great for the battle against COVID. It means we are establishing evidence that we can successfully develop a vaccine. Whether it’s Pfizer or Moderna or another company entirely, I am cautiously optimistic that we’ll be able to emerge from the pandemic towards a healthier future. This is going to be hard, but help is available.