Today’s competitive landscape for medical devices is market-driven and outcomes-based. While the regulated medical device industry was traditionally driven by a focus on approvals and reimbursements, it is now imperative that devices appeal to their end users, and that adherence is encouraged. Good user experiences are now a benchmark for success.

On Friday, April 10, Continuum joined Sanofi at MassMEDIC for a panel event focused on this challenge: Designing for Human Behavior—Developing Medical Devices for Regulatory Approvals and Market Adoption

Sean Phillips, Human Factors Principal at Continuum, began by outlining a brief history of human factors, starting in 1993 with the HFE guidelines for the design of medical devices (ANSI/AAMI HE 48), which ultimately evolved in to HE75. Two significant standards were introduced in 2007, including IEC 62366, application of usability engineering for medical devices and ISO 14971, application of risk management to medical devices. In 2011, the FDA created a draft guideline, applying human factors and usability engineering to optimize medical device design. This document, which should be approved in 2015, established frameworks for performing formative and summative usability studies, as well as outlining what should be included in a human factors engineering report.

Sean went on to explain that human factors has traditionally focused on two high-level goals: ensuring ease of use and managing risk. It’s a discipline that encompasses the prioritization of features, shaping of interfaces, and minimization of potential harm to end users.

With this basic understanding of the discipline, Sean provoked the audience to wonder if this traditional view of human factors engineering is enough to deliver on the positive user experiences the competitive landscape requires.

How might organizations engage human factors earlier in the process? Sean argued for contextual inquiry, a process of understanding project stakeholders by with key decision-makers as well as users to uncover their opinions, needs, wants, and emotional responses, and also observing them in the context of their daily lives. This deep user understanding has paid off on projects such as the Insulet Omnipod, a patch pump which delivers insulin to people with diabetes, while minimizing the condition and allowing them to live active lives, which has sold over 20 million units.

Next, Ulrich Bruggerman, Head of Academics and Innovation MED at Sanofi, opened with a story about his father. They were driving together when his father told him he had never changed the station on his car radio because he didn’t know how. Ulrich tried as well, and resorted to referring to the owner’s manual for the solution. That’s not a good experience, and a similar line of thinking applies to the pharmaceutical industry.

Ulrich titled his talk, “The Success of Your Product Relies on Its Users.” He urged the audience to consider end user(s)—there may be more than one. It’s important to consider healthcare professionals, patients, their families, etc, and also think about their past experience with specific products. Could it be translated to a new product? It also represents a change in attitude to ask yourself, will my product actually serve my users?

This can be validated through analyzing interactions, identifying all possible errors and difficulties, controlling risks, running tests, and revising design.

It’s also key to understand the market. What else is out there?

Ulrich detailed the Lovenox pen, a disposable, fixed-dose pen for heparin, which patients self-administer after day surgeries. It was developed 4 years ago, and offers some effective human factors design: it’s a simple design with arrows to show patients what to do. The pen failed testing, however, because it needed a priming step, a part of the process not needed every use and not indicated on the device. Later, Sanofi developed a similar device, but it was clearer about the priming step. This pen is currently on the market in Europe.

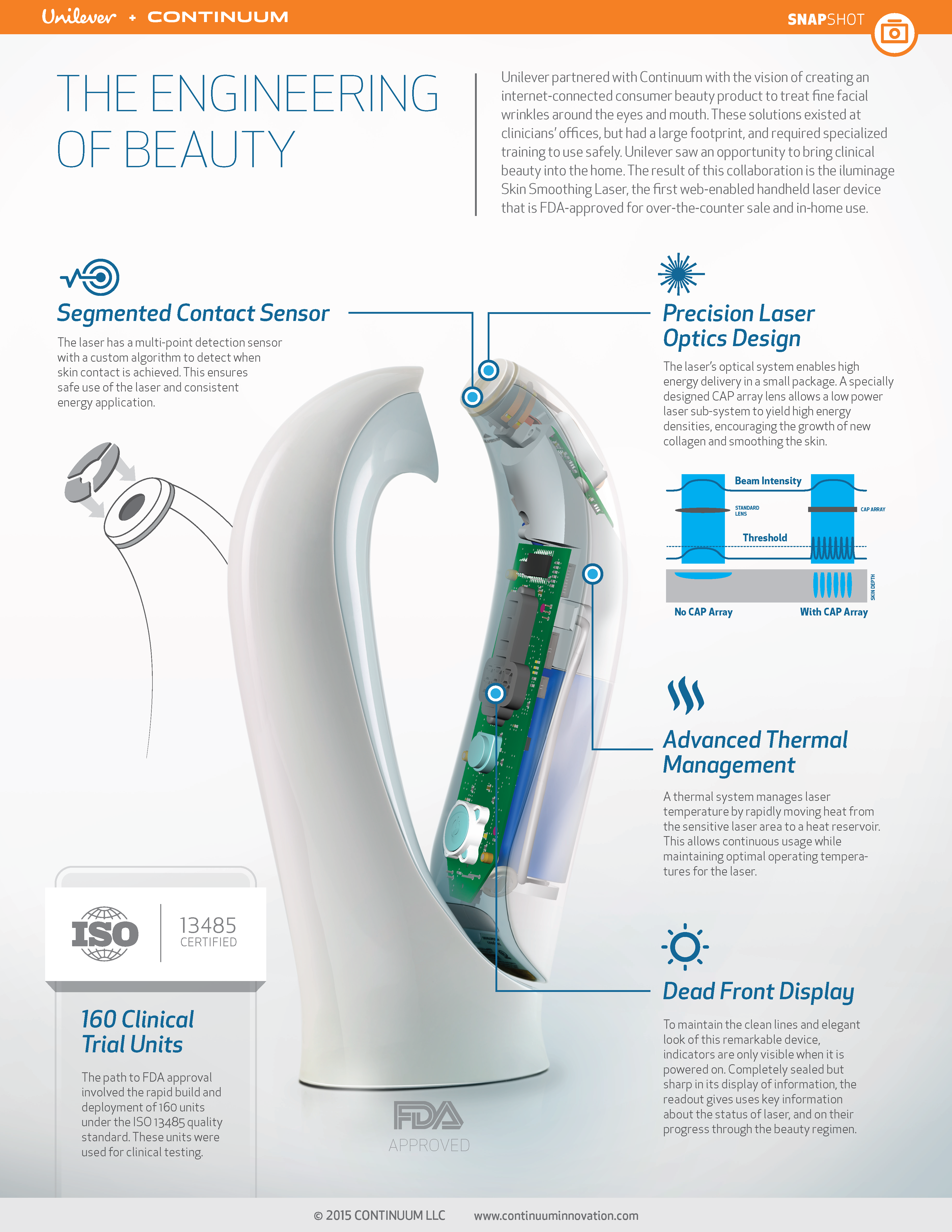

Lastly, Kevin Young, SVP Product Experience at Continuum, outlined our project story of the iluminage Skin Smoothing laser, developed in partnership with Unilever and a specialized technology partner. The story focused on putting users at the center of the development approach. The complex technical development of this consumer beauty product was informed by human factors experts and contextual inquiry. Members of this cross-functional team were engaged throughout the process, rather than engaging HFE at the end of the timeline.

This project focused heavily on contextual inquiry, including techniques such as consumer ethnographic research as well as stakeholder interviews. The team got people responding to sacrificial concepts (a method called mock use).

Early results pointing to the success of this product are positive; it launched in the fall of 2014 and is currently sold in high-end department stores in the US and Europe, including Sephora, Neiman Marcus, and Harrod’s.

Any time we are designing in the regulatory environment, whether for over-the-counter sale, post-operative treatment, or use in a clinical environment, it’s no longer enough to simply develop products and technologies that function properly, mitigate risks, and are easy to use. Human factors engineering is recognized as a sophisticated discipline, but is still critical that HFE teams be engaged early in the design process, so they can be a part of contextual inquiry and other key development activities.